Earlier this week something about Stanley Ginsberg’s version of a rye from the Lithuanian resort of Palanga seemed to call to me. Maybe it was his summary description:

This is an exceedingly versatile bread that will go with pretty much anything savory: my own preference is for what I call “Baltic sushi” – a slab of lightly buttered rye, topped with herring and sliced red onion.

Or maybe it was because although the process looked complicated, I could see that it would result in a relatively easy-to-handle dough, which would make a nice change. Either way, it seemed worth a shot. My only misgiving was that my rye flour is wholemeal, rather than the light rye that the official recipe wants. ((The flour is Italian and stone-ground, from Viva, and I love it. It has a Falling Number of 220 sec, according to the website, which is pretty good.))

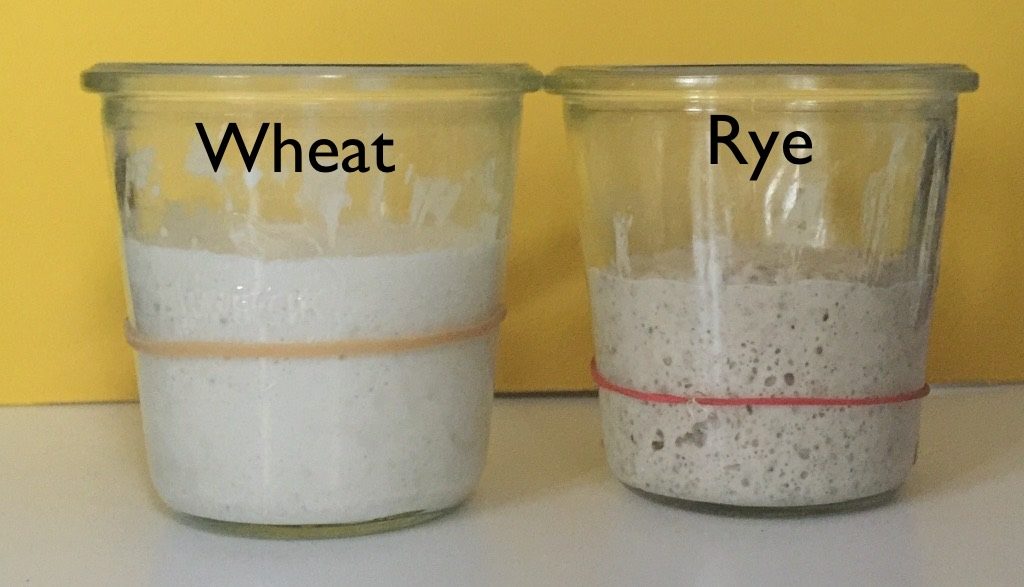

Anyway, I decided to give it a go, ((As usual, when I am strictly following someone else’s recipe I don’t give details here. Better you go to the original and grant the author the traffic.)) starting on Wednesday night, feeding my 100% hydration wheat leaven with rye to create the rye sour that the recipe needs to begin. ((Not sure how sour it is. Not very. I think it’s just a matter of terminology.)) The main lesson here was a vivid demonstration of how much livelier a rye leaven is than a wheat leaven. The rye roughly tripled, while the wheat barely doubled.

As a result, I was ready to begin the recipe proper, on Thursday morning, with the natural rye sponge. Five grams of starter seems far too little, but it did its job, and of course one of the fine side-effects of too much starter is a pancake for lunch.

As a result, I was ready to begin the recipe proper, on Thursday morning, with the natural rye sponge. Five grams of starter seems far too little, but it did its job, and of course one of the fine side-effects of too much starter is a pancake for lunch.

In the afternoon of the first day, you make the scald. Mixing rye flour with hot, even boiling, water, is a standard technique for releasing some of the sugars. (See Black Pepper Rye.) In Ginsberg’s recipe, the water is at 65°C rather than boiling, and one is supposed to keep the scald at that temperature for three hours. I quickly discovered that even on the lowest setting, my oven was hotter than that, but making use of the thermal capacity of the baking stone and checking every half hour or so I was able to be a human thermostat and keep things at around that level. One more misgiving; only 2 gm of caraway seeds?

As forecast, the scald became quite liquid during that time, and developed a delicious, somewhat sweet, somewhat earthy aroma. After cooling the scald for an hour, I dumped the now well-risen sour onto it and mixed with my strongest spoon. Ginsberg says this is called an opara. Next morning, having been covered and left overnight, it had bulked up quite a bit and now smelled beery (malty?) rather than earthy.

Early on Friday, while the morning cuppa was brewing, I threw together the final component, a yeasted rye sponge, so that it would be ready at about the same time as the opara.

Came the moment to mix the final dough, which now gained 100 gm of bread flour, a fraction over 10% of the total flour. It all came together beautifully and despite being tacky in the way that rye doughs always are was not difficult to knead. In the end I stirred for about three minutes to get the wheat flour in, another three to get the rye in and a final three minutes kneading the whole.

In a clean bowl, it had risen to double within an hour. I pre-heated the oven and shaped a boule, leaving it to rise again on the peel. After a bit more than an hour, I judged it had expanded enough to go into the oven, and discovered that my water sprayer was clogged. Rome water is so hard. I quickly flicked water over the suface as best as I could and slid the loaf onto the stone.

When I opened the oven door half an hour later the most wonderful deep rye aroma filled the kitchen, all sense of beeriness gone, just that nutty, slightly bitter, very grainy smell. Half an hour after that, I pulled out the loaf and brushed the surface with boiling water. This is new to me, though like the scald common with proper rye loaves, and it was fun to see clouds of steam arising from the loaf, which turned a darker, shinier brown. Not quite a horse chestnut, but getting there.

Palanga rye bread, the morning after baking.

Fine-looking slices, ready for their filling.

Next morning we had a trip planned to the thermal baths, and a sandwich lunch was definitely in order. The loaf sliced quite easily and the crumb was even, soft and moist. All we did for the sandwiches was pile on some mortadella, and the general consensus was that this was most definitely a bread to reckon with. It is chewy, but not tough, and even the tiny amount of caraway comes through, suffusing the taste. The sweetness makes itself apparent later and is a good contrast as it mingles with the earlier flavours of the rye. A definite keeper, this.

I thank the steam from the baths for the dreamy look, which perfectly suited the occasion.