Today, 7 February 2021, sees the start of the Roman festival of Fornacalia, namesake of this website. Curio maximus Farrell Monaco (or should that be Curia maxima?) decreed it so, as is her right. She suggested we bake Bread for the Gods: Mola Salsa; I am not ready for that and so, once again, I baked a very un-Roman bread. I’m sure the Romans knew of rye, but I don’t think they baked with it. Caraway they knew, sunflower seeds absolutely not. Anyway …

This is now the third time I have baked David Kaminer’s 100% rye sourdough. The recipe seems complicated at first glance, but it really isn’t, and I am sharing it here (finally) only because I have successfully reduced the quantities to make two good-sized loaves (about 2.1 kg of dough) and need to have a reference for myself. It takes a while, but very little of that requires any activity. Ideally, if you start to build the leaven on the morning of day one, you will have bread to eat on the morning of day three.

It goes roughly like this:

-

Day one, morning, first build of leaven

-

Day one, late afternoon, second build of leaven

-

Day one, late afternoon, make soaker

-

Day two, morning, mix final dough

-

Day two, 3–4 hours later, bake

-

Day two, allow to cool completely and “settle”

-

Day three, you may now eat your bread

Leaven

- 675 gm at 100% hydration

I build the leaven in two stages. It really does not matter what kind of starter you start with. I generally use my 75% hydration wholemeal starter, but given that it makes up only about 2% of the leaven, it makes no difference.

- 15 gm starter

- 30 gm whole rye flour

- 30 gm water

Mix up the first build of the leaven and leave to double or more in volume. Mine usually takes about 6 hours to do so.

- 75 gm leaven

- 300 gm whole rye flour

- 300 gm water

About 4–5 hours before bed time, build the leaven again. It wants some time at room temperature before you put it into the fridge to continue fermenting overnight.

Soaker

- 140 gm whole rye flour

- 140 gm toasted sunflower seeds

- 9 gm caraway seeds

- 20 gm salt

- 145 gm water

- 70 gm old bread

I usually make the soaker immediately after the second build of the leaven and, as per David Kaminer’s tip, I make it in the final mixing bowl, because cleaning.

The only tricky part is the old bread. If this is your first time, you might not have any. That doesn’t matter, just leave it out, but try to save 3 or 4 slices from this bake for the next time you want to make this recipe, which you will. It adds a lot of depth. David is suitably vague about the amount of old bread, but I have found that 70 gm of dry bread is good for me. At the very start of the process I put it into a jug of water to absorb all the water it can.

Toast the sunflower seeds, either in a big skillet or under a grill, until you get a good whiff of that nutty aroma. Mix with the flour and salt. Add the old bread, squeezed, but not too much, and broken up as best as you can. Then add the water and stir everything to combine well. Cover and leave to stand overnight.

Final dough

- 675 gm leaven

- 525 gm soaker (approx.)

- 450 gm whole rye flour

- 470 gm hot water (40°C)

- Loaf tins

Before you begin, prepare your loaf tins. Mine are quite small in cross-section, and I keep meaning to invest in some larger ones, but thanks to Brexit I can’t get the ones I should have got last year. No matter. Although the tins are supposedly non-stick, a decent coating of oil helps a lot.

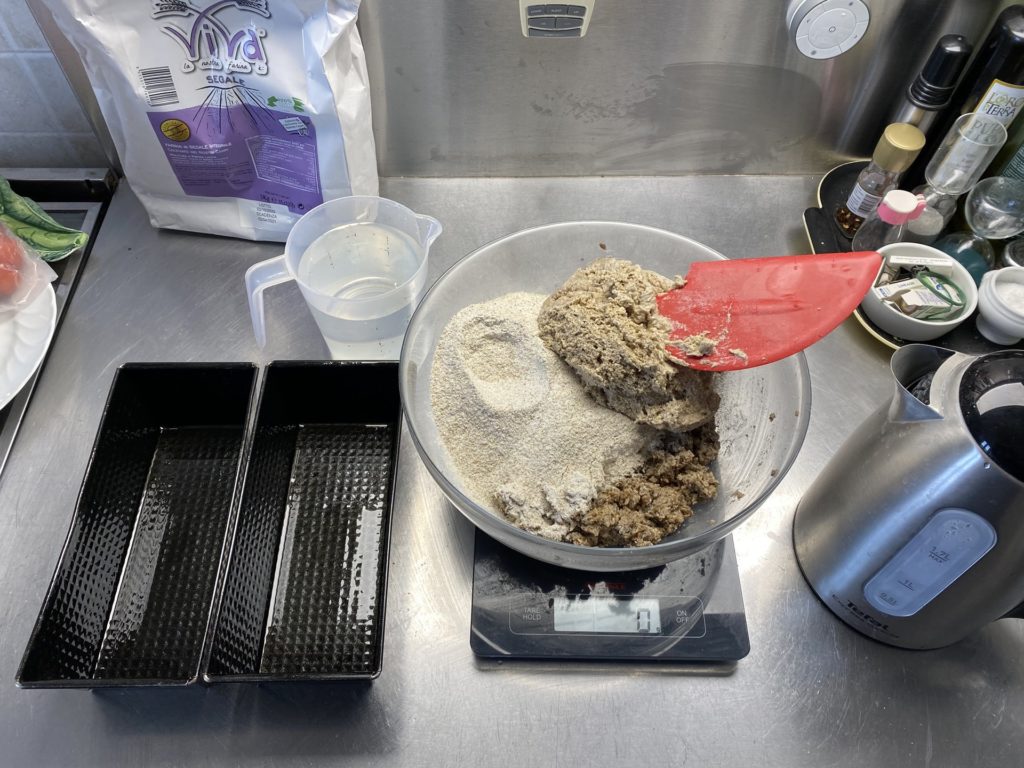

Remove the leaven from the fridge and add it to the soaker in the bowl. Add the rye flour and the hot water. (I have a kettle that tells me the temperature of the water, so I set it to boil and remove it when it hits the mark.) Measure the water and pour it into the bowl. Now things get sensuous.

Keeping one hand clean and a scraper handy, squidge the dough through the fingers of your other hand. The video here shows exactly what I mean. You cannot knead this dough, but you do need to ensure that it is very well mixed. It feels somewhat strange at first because the water is hot and the leaven is cold and you move from one to other in unexpected ways. Soon, though, the whole thing is of an even consistency and temperature.

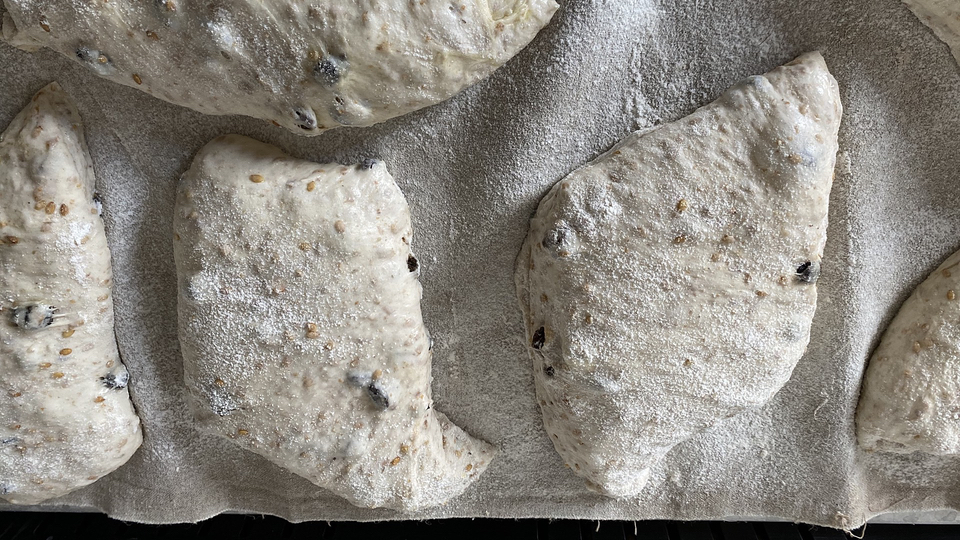

Scrape your hand clean and then persuade the dough into the tins. I like to use a scale to ensure that the tins contain the same amount of dough. With wet fingers, pat the dough down to level it in the tin. Now sift a little rye flour over the top of the dough, aiming for a light and even covering.

Put the tins somewhere warm to rise. They are ready when you can see nice cracks opened up in the rye flour, but in truth in my tins the dough only rises about 1 cm, if that.

Preheat the oven as hot as it will go, starting roughly when you notice the first small cracks in the rye flour. The loaves will be ready to bake 45 minutes or so later.

Bake at about 245°C for 20 minutes, then lower the temperature to about 205°C for another 60–70 minutes. Remove the tins from the oven and allow to cool for about five minutes before extracting the loaves and then allowing them to cool on a rack for at least 18 hours. Most bread, and especially rye bread, is a lot tastier after it has been allowed to cool properly, and rye needs a good long while to become soft and moist rather than gummy.

At some point before you finish the loaf, cut three or four slices and allow them to dry before putting them somewhere safe, so that next time you can add the old bread as you should.